See what Lake Mead’s extreme drought has exposed

December 16, 2022

Lake Mead, Nevada — On a desolate spot on the southwestern shore of Lake Mead, a rattlesnake crouches in a pile of rocks, just feet from the remains of an abandoned boathouse baked in the desert sun.

The wreck is littered with remnants of a bygone life: cracked white plates surrounded by delicate floral patterns, coffee cups set far from matching saucers, blenders filled with dust. Its wooden frame was splayed across an uneven bedrock, split beams and rusted engine parts woven with rope and wire. A small white toilet sits on top of the ruins. Its base – still attached to the lid – can be found near the water.

Earlier this year, the boat was submerged underwater in Emerald Lake.

But the formerly sunken ship, perched high on the horizon, has become a sign of the lake’s new reality as it emerges from one of America’s most dire climate crises — an extreme drought in the West.

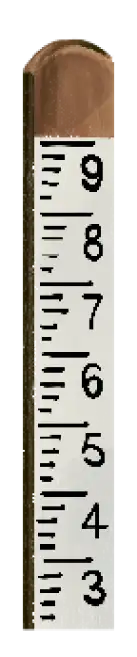

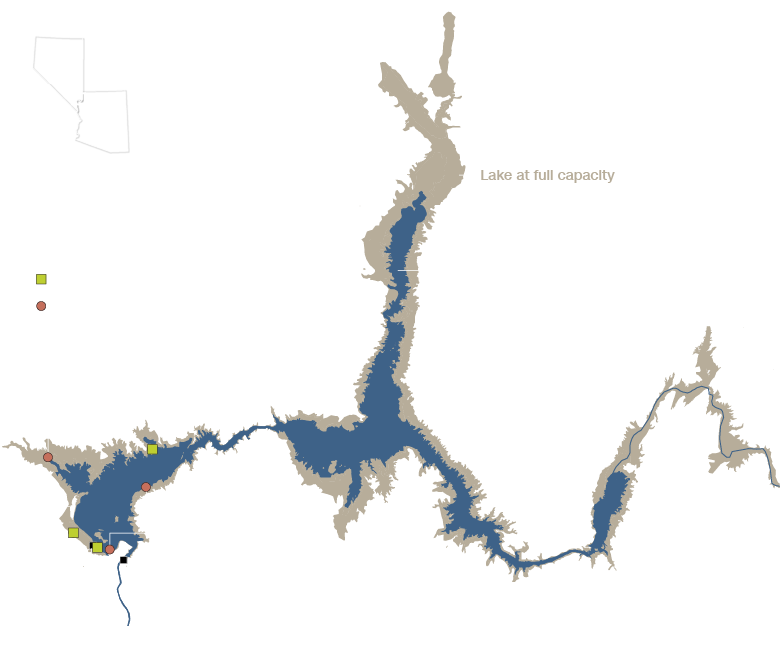

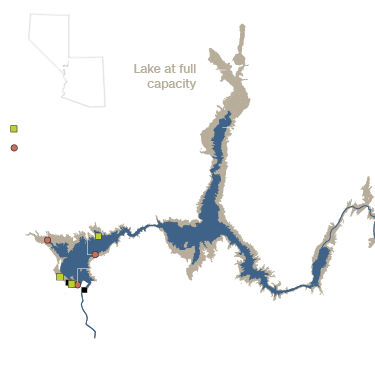

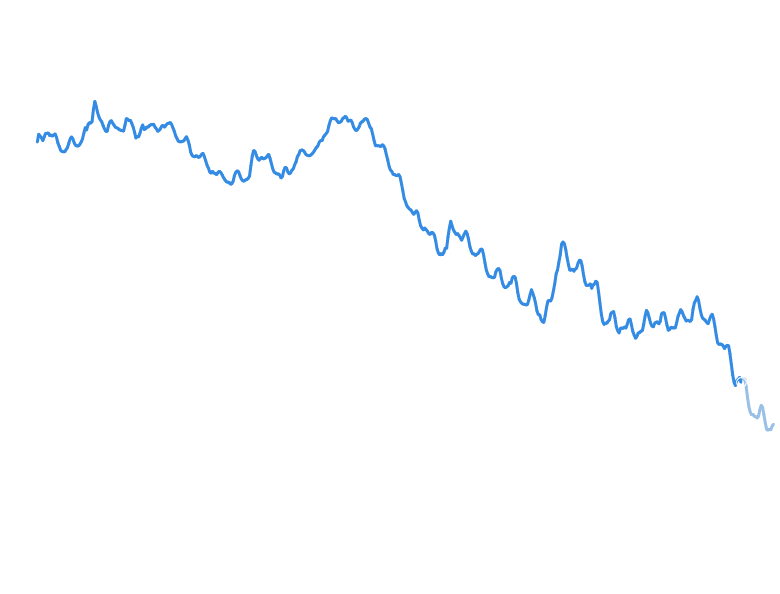

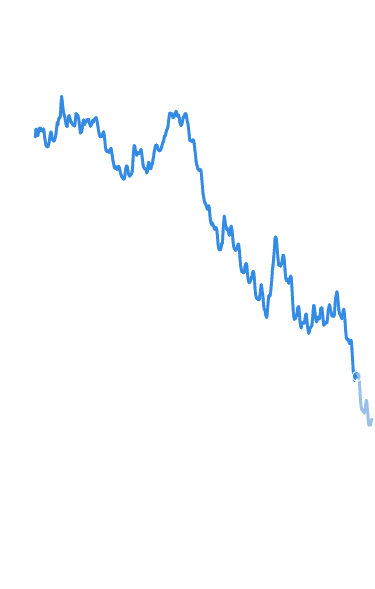

Due to a decades-long “megadrought” in the region, Lake Mead’s water level has dropped by about 170 feet since 2000, causing its shoreline to recede dramatically and exposing large swaths of its dry lake bed. Some locals and long-time visitors believe the problem has made life by the lake seem trivial compared to what it used to be. But the crisis is also attracting a new kind of tourist — tourists who come to see all that the newly exposed coastlines have to reveal.

Designated the first National Recreation Area in 1964, Lake Mead’s mirrored lake and stunning mountain vistas draw throngs of tourists who meander across the water in small boats and jet skis, holding Towels trek to shore. Yet if the reservoir’s water level drops to an all-time low, the scene will be far quieter than the boaters’ paradise Joyce DiManno remembers.

A longtime resident of Boulder City, near the park, DiManno has views of Lake Mead and its mountains from the expansive windows that span her living room.

“We’ve lived in this house for five years and it’s been amazing to see the water continue to disappear in the front yard,” she said.

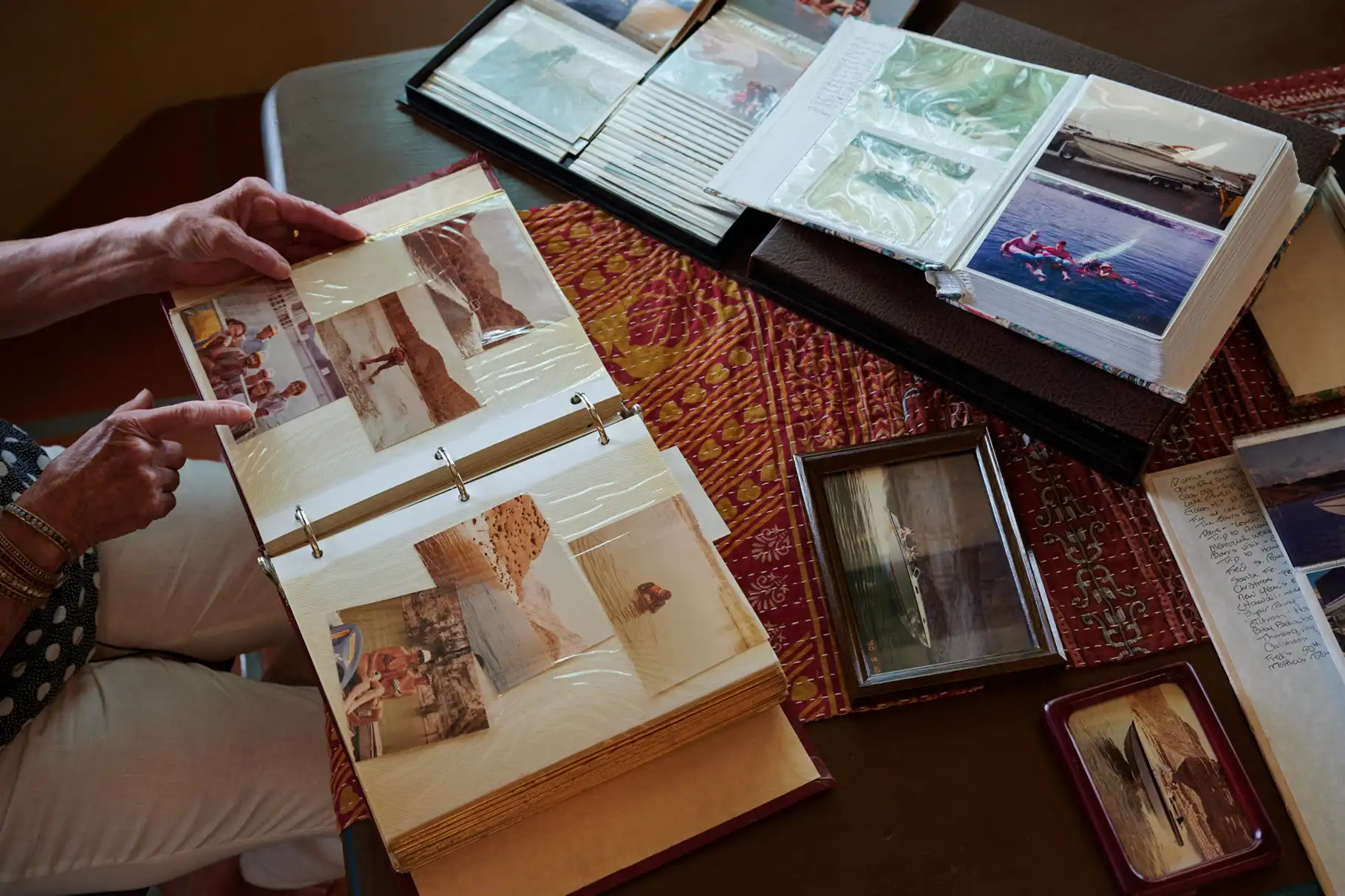

Sitting at the kitchen table, Dimeno spread out in front of her stacks of photo albums, each containing photos from the ’80s and ’90s that she and her husband, Frank, took religiously touring the lake.

As she combs through them, she points to snippets of weekend skiing and boating with friends, as well as countless hours lounging on the coves and beaches. At that time, the drought was far away from them.

The Dimenos eventually sold their boat in 1999. Over the next few years, the couple were front-row viewers as many of their beloved attractions were transformed beyond recognition.

On Boulder Beach, southwest of the lake, the shoreline has receded so much that the road built to meet the water’s edge ends abruptly several hundred yards from the waterline. Cars laden with folding chairs, umbrellas, kayaks and mounds of food must navigate the rough off-road to shore, their wheels rolling over delicate white shells on the dry lake bed.

The newly exposed shoreline near Boulder Beach was the site of a shocking discovery earlier this year, when the body of a decades-old homicide victim was found inside an eroded barrel that was likely Was thrown far offshore in the 70’s or 80’s. Over the next few months, several more remains were found in the receding waters, including the body of a man who drowned in 2002.

As water levels drop in this major lake, dead bodies start showing up

News of these discoveries, along with the revelation of artifacts such as World War II-era landing craft, catapulted the reservoir’s water shortage into the national spotlight, attracting a motley mix of amateur treasure hunters, YouTube explorers and curious tourists hoping to discover the reservoir. Now scattered across the dry lake The remains of the bed.

Near the busy wharves of Hemenway Harbour, the wreck of a sunken Higgins ship from World War II has become one of the more recognizable antiquities to emerge from the receding waters. Its ribbed frame rises from the water like the washed-out skeleton of a prehistoric fish. The longship has been partially destroyed and its engine removed.

Muddy waters and layers of silt obscured the rest of the ship’s U-shaped design, which the park said was still clad in armor plates. Its body is covered in thick bands of rust, covered with underwater life and tiny shells.

The amphibious landing craft are designed to transport U.S. troops from ships to open beaches, but the ships have long been used around the park. The park service isn’t sure how or when the ship was parked there, but the shallow waters have become a pilgrimage site for curious explorers.

Another sleek vessel that draws tourists bursts out of the ground at what appears to be an anti-gravity angle. The boat was partially submerged in May, but with its engine firmly lodged in the accumulated silt, it remained upright even as the surrounding lake water disappeared.

Dozens of other previously waterlogged boats are now nestled among clumps of friable bushes or anchored on sandy shelves formed by the falling shore. Most are covered in layers of grime and underwater life clinging to the control panels. The few that do appear to be intact, as their glossy paintwork glistens in the sun and appears to have survived years of underwater immersion unscathed.

The true scale of water loss can be seen from almost every vantage point in the reservoir. Towering rock formations protrude from the water and surround the lake, lined with thick streaks of white sediment left by past water levels.

The distinctive “bathtub ring” across the mountains can be seen even from a distance.

The ivory ring sits flush with the top of the hulking Hoover Dam, which holds back the reservoir’s flow. Today, the dam’s towering turbines—capable of producing enough hydroelectric power for an estimated 1.3 million people a year—jump out of the water. They can only run at slightly more than half capacity if there is not enough supply. According to the Bureau of Reclamation, if the water level drops another about 100 feet, they will no longer be able to generate electricity.

Although water levels have been drastically reduced, the reservoir still provides a remarkable playground for millions of visitors each year. However, getting the boat out on the water is becoming increasingly difficult.

Since 2000, the National Park Service has spent nearly $50 million relocating and expanding boat launch ramps and other infrastructure in an attempt to chase the waterline. But even with these huge and costly adjustments, the park was forced to close all programs, and a catastrophe struck.

On the only remaining launching ramp in Haimenwei Harbor, the water is still too shallow for large ships to enter. On busy days, wait times can stretch into hours, as cars hauling boats and trailers clog the road to the water. The long, paved runway to the ramp is marked from time to time with signs warning of the risks of boating in low water.

When Alan O’Neill was superintendent of the park from 1987 to 2000, the park maintained as many as nine ramps for people to pull boats in and out of the lake, he said, adding that the park had Only one ramp is “miserable.”

“It breaks my heart to walk there,” he said. “We think it’s almost impossible for the lake to reach the level it is now.”

While O’Neill is quick to point out that the 1.5-million-acre park still offers a wealth of on-land recreation among its vast expanse of mountains, valleys and canyons, he believes visitors’ experience at the lake has been severely impacted by the closure of facilities such as launch Ramps and piers.

“It was really sad to see the view outside because I know how many people in our community love not only the lake but the nearby shoreline,” O’Neill recalled of the bustling activity at the park.

News of the extreme drought affecting the lake may also deter tourists who think the picture has turned bleak, said Bruce Nelson, director of operations for the Lake Mead Marina in Port Hemenway.

“Everyone believes Lake Mead is one big mud hole, but it’s not,” he said, emphasizing that even at its low capacity, the reservoir remains one of the largest in the United States. “It’s still a great lake for boating and relaxing.”

Aware of how water and hazard conditions can affect the visitor experience, the National Park Service has held several public meetings this month and is developing a plan to accommodate boating as the reservoir descends.

Recent federal forecasts show that reservoir levels are expected to continue to decline over the next two years, approaching levels in the “dead pool” where the dam cannot release water downstream. The dire forecast has already prompted the federal government to impose water shutoffs in Nevada, Arizona and Mexico. California may soon follow.

Still, further cuts are needed to protect Lake Mead and the Colorado River basin. Yet negotiations between states, tribes, cities and farmers have been tedious as they decide who will bear the most restrictions.

But the federal government’s patience may soon run out if states fail to commit to large enough water savings. The Interior Department is preparing to take action of its own, which could include restricting the release of water downstream from the reservoir to prevent it from approaching stagnant pool levels.

Although Joyce DiManno no longer boats at the reservoir, she still makes occasional visits to stroll along the ever-expanding shore. She hopes the lake will avoid reaching crisis levels, but she doubts it will ever be as bustling as she remembers it.

“Will it be like it used to be? No,” she said. “I really feel like we had the golden days of boating there. It’s just amazing.”

“We never thought we’d see something like this (happening) at this time,” DiManno said.

If the falling water persists, unexpected vestiges of the reservoir’s past will continue to be revealed. But at depths that can extend hundreds of feet deep, decades-worth of artefacts remain submerged.

At Overton Arm, north of the reservoir, the heavy frame of a bomber has been sitting on the bottom of a lake for 74 years after a gross miscalculation of the plane’s altitude caused a B-29 Superfortress to crash into the water and sink into the lake bed.

Once more than 200 feet below the surface, this place is a remarkable trip for divers. But after water levels at the site dropped by about 100 feet, the park restricted diving there entirely this year while deciding how to preserve the historic site in increasingly shallow waters.

Soaked in the depths of the lake for decades, the plane’s aluminum fuselage was covered with invasive mussel colonies. In the sunken cockpit, parachutes are hung between the seats while the crew evacuates safely.

The future of the B-29 and the critical waters around it remain unknown. But for now, the underwater wonders of Lake Mead are getting closer and closer to the surface as time goes on.